Warranty Conference,

Part Five:

With extended warranties, a lack of regulations invites inconsistency. But too much regulation could drive up costs. The SCIC's attorney helps states find a middle ground.

One would normally assume that the companies that offer service contracts would be against regulations. However, in reality the sellers, administrators, and underwriters of service contracts have assumed that regulation is both inevitable and perhaps even desirable, if the alternative is an inconsistent business environment that varies from one state to the next.

Last month, Timothy Meenan, a partner in the law firm of Blank, Meenan & Smith P.A., and general counsel of the Service Contract Industry Council, told the attendees of the Warranty Chain Management conference in San Francisco that because insurance is regulated at the state and not the federal level, the best one can hope for would be a set of 50 somewhat consistent state laws.

Extended warranties are something of a hybrid: treated as specialty insurance by some, and as maintenance agreements or product guarantees by others. Plain old product warranties, meanwhile, are regulated somewhat at the federal level, somewhat at the state level, and somewhat not at all (at least compared to insurance or real estate). One federal law covers only warranties offered to consumers, and then only those offered in writing. In some states, the regulatory treatment of something as simple as a washing machine's service contract would change depending on whether it was sold to the consumer by a retailer at the point of purchase or by a home warranty company at the time the house changed hands.

Avoid Extended Warranties?

Meenan told the near-capacity audience that he tries as much as possible to avoid using the term extended warranty. That term invites people to get confused, he said, because they may think of the extended warranty as literally an extension of the manufacturer's product warranty. Warranty Week notes that some newspapers rather regularly confuse the terms, referring to an automaker that lengthens its product warranty from three years to four as the provider of an extended warranty. We prefer the terms lengthened or enhanced, but even in this article we can't avoid use of the phrase extended warranty.

Don't get us started. Last year, one company asked Warranty Week to not only avoid using the phrase extended warranty, but also to remove the word insurance from any articles about their service contracts. They seemed worried that it might one day be Googled by some insurance commissioner who would then wonder why this type of insurance isn't regulated like life, health, or homeowner insurance. And then there are all the manufacturers who avoid complying with all the new warranty and extended warranty accounting rules by simply denying that they sell anything but prepaid maintenance agreements.

Meenan listed additional reasons why he avoids the phrase. He said he fears that use of the words "extended warranty" could draw the administrators or retailers who sell them into class action lawsuits having to do with product liability issues. Service contracts should be focused more on whether or not to pay for a repair. Product warranties are more of a statement of guarantee that a product is free from defects. And then there are the implied warranties of fitness for a particular purpose and of merchantability, which have provided fertile ground for lawsuits, even where the products were sold with no written warranties. Again, don't get us started.

But what seemed to concern Meenan more than the threat of attracting ambulance-chasers was the possibility that regulators might one day begin to treat extended warranties as just another form of insurance. That would exponentially increase the amount of regulation faced by the industry. Some states could regulate prices, or they could cap profit rates. Others could require those who ask, "would you like to buy the warranty?" to be licensed by the state only after they pass a rigorous exam. And those who don't comply with the letter of the law could find themselves facing court injunctions, fines, or possibly even jail time for selling insurance without a license.

"Stating the obvious, if it's insurance, then you need to have licensed insurance agents out on the retail store floors," Meenan told the conference. "That is one big drawback to being declared insurance."

Meenan said there actually are such things as call centers staffed with telemarketing agents who also are licensed as insurance agents, but they are among the most expensive of all call centers to run. Furthermore, it takes hundreds of hours to get an agent licensed, fingerprinted, and trained, which when combined with the high turnover that's typical of call centers, would further drive up labor costs.

Insurance Rate Regulation

In addition, in some states details of insurance rates as well as quarterly income statements must be filed with regulators. In others, insurance rates are regulated in a way that caps profits at 10% to 15%. The profitability level of extended warranties has always been a closely-held secret, but we note that if the sales commissions are typically 40% and up, somebody must be making money. Suffice it to say that rate regulation would not be a welcome development if it reduced these commissions.

Meenan said that before the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act was passed in 1975, service contracts were viewed simply as warranties, and were therefore only lightly regulated, if at all. "The key distinction, of course, is there's separate consideration. You're selling it, and collecting a fee for it, which is not what Magnuson-Moss really envisioned," he said. But federal law was never changed to keep up with these changes.

The Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act defines a written warranty as follows:

"The term 'written warranty' means: (A) any written affirmation of fact or written promise made in connection with the sale of a consumer product by a supplier to a buyer which relates to the nature of the material or workmanship and affirms or promises that such material or workmanship is defect free or will meet a specified level of performance over a specified period of time, or (B) any undertaking in writing in connection with the sale by a supplier of a consumer product to refund, repair, replace, or take other remedial action with respect to such product in the event that such product fails to meet the specifications set forth in the undertaking, which written affirmation, promise, or undertaking becomes part of the basis of the bargain between a supplier and a buyer for purposes other than resale of such product."

Further down, the Act defines a service contract as "a contract in writing to perform, over a fixed period of time or for a specified duration, services relating to the maintenance or repair (or both) of a consumer product." Therefore, it was entirely possible for a written promise to repair defects to be both a warranty and a service contract at the same time. Nowhere did it say that warranties are free while service contracts are sold separately.

Reducing Ambiguity

Eventually, Meenan said, state insurance industry regulators took another look and found that service contracts seemed to also fit within their definitions of indemnities: "An agreement to pay a specified amount upon a determinable contingency." That would mean they should be treated like insurance contracts. In an effort to head off the regulation of the business as part of the insurance industry, the Service Contract Industry Council was formed, initially as a division of the North American Retail Dealers Association.

"We had to respond legislatively," Meenan said, "so we developed a model act regulating service contracts. You can think of it as a 'carve out' from the insurance code. That's really what we're after, because we did not want to be in the insurance code." But because insurance is regulated in the U.S. at the state level, such a process would entail the lobbying of 51 different legislatures (D.C. too) and the passage of 51 different service contract laws.

In a perfect world, the 51 laws would be different in name only. Ideally, sellers and administrators of service contracts would want to do business across state lines, facing a consistent set of laws from one state to the next. The model act was a template that could be handed to legislators who were thinking about drafting service contract industry regulations.

Enter Tim Meenan as the general counsel of the SCIC. His role would be not only to function as the personality holding the organization together, but also to serve as the liaison and the legal representative of the SCIC to the states. And the SCIC's goal was to make sure that service contracts were not regulated like insurance.

The model act, Meenan said, defines a service contract as one that promises in writing to perform over a fixed period of time or for a specified duration, services relating to the maintenance or repair (or both) of a consumer product or real property. It must relate to a defect in materials and workmanship, and not to perils outside the product. And it must be priced separately from the product.

Broadening Definitions

In some states, Meenan noted, the definition of a service contract has broadened over the years. For instance, service contracts that cover defects in the materials and workmanship of automobile tires nowadays also frequently cover punctures. "It's not really a defect in the tire when you run over a bed of nails," he said. Nevertheless, just last year regulators in California agreed that service contracts covering road hazards did not cross the line into the world of insurance.

The key point, Meenan said, is that the modern definition has expanded to allow for limited indemnity, "as long as it's ancillary to what you're doing." In other words, it's still a contract that primarily covers defects in materials and workmanship. It's not part of an automobile collision or liability insurance policy.

The model act suggests requirements for the licensing of the sellers and/or administrators, as well as requirements for solvency, record-keeping, and disclosure. For instance, administrators have a choice of three ways to meet solvency requirements: having a net worth of $100 million or more; self-insuring by reserving a suggested 40% of the retail price to cover future claims (and depositing 5% with the regulator); or obtaining contractual liability insurance from a regulated carrier to cover 100% of claims.

Of the three, the fully-insured option is the most common, Meenan said, with the self-insured option on the wane, and the net worth option followed by a steady minority of well-heeled industry players. But there are lots of exceptions. Oregon doesn't allow the self-insured option at all. Others change the 40% reserve rule to 25% or some other number.

The Regulatory Landscape

Meenan then mapped out the regulatory environment of the 50 states by placing them into one of four categories:

- Regulated - covered by a law based upon, or similar to, the SCIC's model act;

- Insurance - service contracts and their sellers are regulated as insurance;

- Dealer Obligor - if the party obligated to pay claims is either the manufacturer, distributor, or the retail dealer, it's not insurance, but if the obligor is a party outside the distribution chain, it's insurance; and

- Unregulated - no laws regulating service contracts as either insurance or not.

He repeated this process three times, once each for vehicle service contracts, for home warranties, and for service contracts covering consumer goods. The reason is that some states treat service contracts differently depending upon the product being covered. For instance, in Pennsylvania a service contract for either consumer electronics or for vehicles would fall into the "dealer obligor" category. But home warranties are treated as insurance.

Each of Meenan's maps followed a similar color-coding scheme, in which green was a signal that the state has passed a law either based upon or similar to the SCIC's model act. These states avoid rate regulation and does not treat service contracts as a form of insurance. The red states are the ones that do treat service contracts as insurance, making it costly and difficult for SCIC members to do business there. And the yellow states are somewhere in the middle.

Meenan said efforts are now under way to introduce or modify service contract laws in New Jersey, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Minnesota. Some are now coded yellow or red, and the SCIC wants to turn them green. Others are white, meaning that there's no definition and plenty of ambiguity. And still others are green on one map, red on another, and yellow on the third, implying a somewhat inconsistent regulatory environment.

Vehicle Service Contracts

For motor vehicle service contracts, also known as service plans, vehicle protection plans, and yes, even as extended warranties, Meenan said there are seven dealer obligor states and one insurance state. In the chart below, the color code for New Hampshire has been recently changed to yellow, and is no longer red. Only Alaska now treats vehicle service contracts as insurance, Meenan said.

Figure 1

Vehicle Service Contract Landscape

Source: Tim Meenan

Each state that contains an "R" symbol is one in which the legislators have overtly settled the status of vehicle service contracts, possibly by passing a law based upon the template of the model act. In 38 states, legislators have definitively decided that vehicle service contracts should not be regulated as insurance. In Alaska, the law says VSCs are insurance. And in 11 states there's been no definitive ruling either way.

Home service contracts, better known as home warranties, are covered by a somewhat different set of laws. If Meenan has a problem with misuse of the word warranty, this must be even more problematic. Home warranties don't warrant the home. They warrant the major appliances, the heating and cooling, and sometimes the garage door opener. But they don't warranty the windows or walls against leaks, the foundation against cracking or settling, or the floors against warping.

"Typically what you see is a program that covers the major appliances and the HVAC," Meenan noted. "Most programs do not cover structural, like roofs, walls, plumbing, or exposed wires -- although those sorts of programs exist." In some states, the majority of used homes become covered by a home warranty as part of the sales process. Sometimes even new construction is covered by a home warranty, usually offered by the builder to provide coverage above and beyond the traditional product warranty.

The typical home warranty covers appliances in the home, which also may overlap with coverages provided by the manufacturer or the major appliance retailer. In some states, the sellers of home warranties are required to file a separate registration with the regulator. In others, one registration allows sellers to offer VSCs, home warranties, and/or service contracts for consumer electronics, computers, appliances, etc. In states such as Illinois, Meenan said, one registration allows a seller to offer all three. But in Florida and Oregon, each of the three types requires a separate registration.

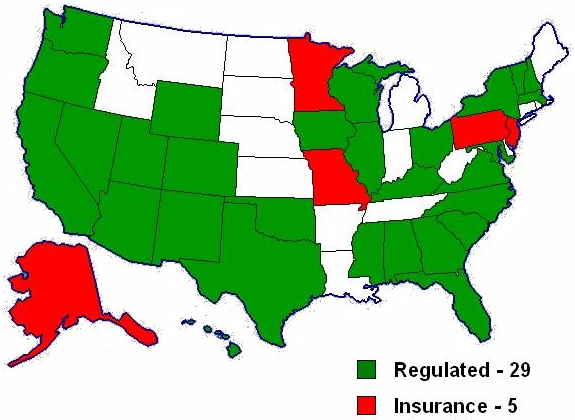

As the chart below illustrates, 29 states regulate home service contracts. Five would qualify as both insurance states and as dealer obligor states, Meenan said, and are denoted in red. And then 16 states are unregulated as far as home service contracts are concerned.

Figure 2

Home Warranty Landscape

Source: Tim Meenan

"There are four or five 'problem marketing states,'" Meenan said, "where home warranty laws allow only licensed realtors, licensed insurance agents, or potentially employees of the warranty company to solicit and sell." An example is Texas, he said, or until recently California. Regulations are constantly changing in one state or another, he noted, which makes this segment the toughest of the three to harmonize nationally.

As far as consumer goods goes, Meenan said there are 26 states that regulate service contracts, as depicted on the map below. There are an additional eight in which dealer obligor is the rule. And then there are 16 where there are no regulations specific to service contracts.

Figure 3

Consumer Goods:

Service Contract Landscape

Source: Tim Meenan

Meenan said that lately the trend among sellers and administrators of service contracts has been to expand their offerings in ways that -- as for tires protected against road hazards -- come very close to stepping over the line into insurance. Increasingly, sellers will offer coverages such as accidental damage protection that have little or nothing to do with product defects and everything to do with perils normally covered by insurance policies.

Will it or won't it be treated by regulators as insurance? What about when one company sells a policy that covers defects, damage, and perhaps also theft? By his maps and his examples, Meenan detailed how these questions will have to be answered one state at a time, hopefully with an eye towards some form of national consistency.

| Go to Part One: Opening Keynote Speeches |

| Go to Part Two: AIAG Early Warning Standard |

| Go to Part Three: Extended Warranties 101 |

| Go to Part Four: Customer Loyalty |

| This is Part Five: National Regulatory Trends |

| Go to Part Six: Auto Warranty Fraud |

| Go to Part Seven: PC & Appliance Warranty Fraud |

| Go to Part Eight: Warranty Metrics |

Part Four: Your best customers buy extended warranties. And the proper administration of extended warranties can boost customer loyalty. Two top executives explain how it's done.March 29, 2005 Warranty Conference,

Part Six: Warranty fraud is a big problem for vehicle service contract administrators. But surprisingly, the biggest culprits are usually the mechanics and repair shops, not the consumers.April 12, 2005