Commercial Aviation Warranty Expenses:

The 21st century of commercial aviation has been dominated by several high-profile warranty problems, from the Boeing 787 Dreamliner delays and 737 MAX groundings, to the Airbus A380 program ceasing. This week, we're taking a look at the history of commercial aviation, and the market conditions and other factors that led to this industry being categorized by extreme periods of warranty costs.

In 2019, Airbus surpassed Boeing in both commercial aircraft revenue and aircraft deliveries. In October 2025, Airbus set another huge milestone in the commercial aviation industry, when its A320 family of narrow-body jetliners surpassed the Boeing 737 series to become the most-delivered commercial aircraft in history.

Airbus and Boeing have defined the commercial aviation industry since the turn of the 21st century. These past two-and-a-half decades in commercial aviation have been categorized by several major and costly warranty problems, which have resulted in high-profile groundings and delays.

Boeing suffered delays in the roll-out of the 787 Dreamliner between 2007 and 2011. Then, despite the delays in production, the aircraft encountered issues with lithium-ion batteries causing fires onboard the aircraft, resulting in a United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grounding for a few months in early 2013. Boeing's warranty costs spiked to record highs during that period, starting in 2011, and lasting until about 2015, though costs remained higher than pre-2011 in subsequent years.

Around the same period, Airbus experienced several delays in A380 production, and once the aircraft were finally delivered, the manufacturer saw a spike in its warranty costs between 2011 and 2014. Delivery delays for the A380 started as early as 2005. The aircraft entered into service in 2007, but an engine failure incident in 2012 caused the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) to issue an Airworthiness Directive and mandate aircraft inspections, which ulimately required Airbus to pay over €200 million to repair cracks in wing fittings and leaky doors.

Just as Boeing began to recover from the spike in 787 Dreamliner warranty expenses, the 737 MAX 8 groundings caused a massive warranty crisis. Because the 737 MAX was a new, more fuel-efficient version of the narrow-body 737 aircraft that had first taken to the skies in 1967, it did not need to undergo as rigorous of an airworthiness approval process as a new aircraft. Of course, the aircraft were grounded globally after two fatal crashes, Lion Air Flight 610 in October 2018, and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 in March 2019. The global 737 MAX 8 fleet was grounded from March 2019 until November 2020. In addition, the next generation, the 737 MAX 9, was grounded by the FAA for about three weeks in early 2024.

To create this newsletter, we gathered data from the annual reports of Airbus SE, and from the quarterly financial statements and annual reports of Boeing Co. We extracted three key warranty metrics: the amount of claims paid, the amount of accruals held, and the end-balance of the warranty reserve fund.

In addition, we gathered data on each manufacturer's total aircraft sales revenue, and used these to calculate two warranty expense rates: claims as a percentage of sales (the claims rate), and accruals as a percentage of sales (the accrual rate).

Airbus and Boeing have essentially had a duopoly over the global commercial aircraft industry since 1997, collectively accounting for about 90% of aircraft sales. But the industry didn't always look this way. And Airbus' dominance is an even more recent phenomenon.

Aviation History: Cultivating the Landscape for 21st Century Warranty Problems

Boeing Co. was founded in 1917. In 1929, Boeing teamed up with jet engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney, to form a large, vertically-integrated aviation conglomerate, including airframe and aircraft engine manufacturers, commercial airlines, cargo airlines, and military aviation. This conglomerate was named United Aircraft and Transport Corp., and encompassed brands including Boeing, Pratt & Whitney, Avion (founded by Jack Northrop), Sikorsky, Chance-Vought, Hamilton Standard, and Stearman, along with airlines Varney Air Lines, National Air Transport, Boeing Air Transport, Pacific Air Transport, and Stout Air Services.

In 1934, the Air Mail Act was passed, in the aftermath of the Air Mail scandal in the early 1930s. This law essentially functioned as an anti-trust law specifically targeted at the aerospace industry, and prevented airframe or aircraft engine manufacturers from owning airlines.

This 1934 law had profound impact on the U.S. aviation landscape, which we still see in the industry today. United Aircraft and Transport's airlines were spun-off into United Airlines. Its manufacturing business east of the Mississippi, including Pratt & Whitney, Sikorsky, Chance-Vought, and Hamilton Standard, were merged into a new company, United Aircraft Corp.; United Aircraft was renamed United Technologies in 1975. Of course, United Technologies was acquired by Raytheon in 2020, resulting in that company's renaming to RTX Corp. (We'll take a look at the warranty expenses of RTX post-merger in next week's newsletter.)

Boeing retained ownership over all of the business west of the Mississippi, including Boeing and Avion. Avion was Jack Northrop's first business (not to be confused with his third business, Northrop Corp., which later acquired Grumman in 1994 to form Northrop Grumman). Boeing retained dominance over global aircraft manufacturing from 1934 until 2019.

The next major move Boeing made, which again hugely shifted the dynamics of the global aviation sector, came in 1997, when it acquired McDonnell Douglas, its largest American competitor in commercial and military aircraft manufacturing at the time.

In the wake of the Boeing acquisition of McDonnell Douglas, several other smaller manufacturers ceased manufacturing commercial aircraft, including Lockheed Markin, Convair (owned by General Dynamics at the time), and the Dutch Fokker, which declared bankruptcy during this period of the mid-1990s.

The end of the Cold War temporarily lowered U.S. defense spending in the 1990s, leading to the market conditions that allowed Boeing to acquire McDonnell Douglas. However, at the same time, another major global European competitor, which had emerged in the golden era of aviation in the 1970s, was gaining its footing.

Boeing's current largest competitor, Airbus, was formed as Airbus Industrie GIE in 1970, a consortium of European aerospace companies. Airbus produced its first commercial aircraft, the A300, in 1974.

In 2000, the Airbus consortium's parent companies, including the French state-owned Aérospatiale-Matra, the German Deutsche AeroSpace AG (DASA), which was owned by Daimler-Benz at the time, British Aerospace plc, and the Spanish state-owned Construcciones Aeronáuticas SA (CASA), merged to form the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company (EADS). EADS officially rebranded as Airbus SE in 2015. However, the commercial aircraft have been produced under the Airbus brand since the consortium's conception.

Deregulation of Airlines: Setting the Stage for Future Warranty Problems

We wouldn't blame our readers for wondering why we're providing this historical background. Shouldn't Warranty Week focus on warranty stories? We would argue that the story of commercial aviation in the 21st century is all about warranty problems, which can be explained by a culmination of circumstances that began in the Western world's emergence from the Cold War in the 1990s.

The 1960s and 1970s are popularly considered the "golden age of aviation." The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, signed by President Jimmy Carter, is largely believed to have led to a decline in the quality of service offered by U.S. airlines. Airlines Pan Am, TWA, and Braniff declared bankruptcy and ceased service in subsequent years, and each remaining American legacy carrier has declared bankruptcy at least once, with the exception of Alaska Airlines. The end of the Cold War temporarily decreased defense spending in the 1990s, further sending the U.S. aeropsace industry into a nosedive.

In 2008, former American Airlines CEO Robert Crandall stated, "The consequences [of deregulation] have been very adverse. Our airlines, once world leaders, are now laggards in every category, including fleet age, service quality and international reputation. Fewer and fewer flights are on time. Airport congestion has become a staple of late-night comedy shows. An even higher percentage of bags are lost or misplaced. Last-minute seats are harder and harder to find. Passenger complaints have skyrocketed. Airline service, by any standard, has become unacceptable."

Furthermore, Crandall stated, "Three decades of deregulation have demonstrated that airlines have special characteristics incompatible with a completely unregulated environment. To put things bluntly, experience has established that market forces alone cannot and will not produce a satisfactory airline industry, which clearly needs some help to solve its pricing, cost, and operating problems."

The 21st Century Commercial Aircraft Industry: Defined by Warranty Problems

Many would argue that Boeing acquiring of McDonnell Douglas in 1997 directly led to the 737 MAX 8 groundings of 2018 to 2020, and the 737 MAX 9 groundings of 2024. Please take a look at these two linked Warranty Week newsletters for more information on these groundings.

Airbus more than doubled its annual deliveries in the mid-1990s. Boeing acquired defense contractor Rockwell in 1996 for $3 billion, and military and commercial aircraft manufacturer McDonnell Douglas in 1997 for $14 billion. Boeing rebranded the new MD-95 as the Boeing 717, and committed to bringing it to market. Only 155 were sold. Then the 2001 World Trade Center attacks occurred, shaking the world, and especially the global aviation sector.

Many executives from McDonnell Douglas retained their jobs in the merger. This is important to note because McDonnell Douglas took a unique approach to the development of the MD-95 — later the Boeing 717 — which significantly shaped the development process of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.

After 9/11, Boeing wanted to design a new wide-body jetliner to better compete with Airbus, as sales of the 747 and 767 slowed, and boost revenue after the 2001 market crash, and the subsequent increase in oil prices. The company gathered together its suppliers and subcontractors, including Vought, Rolls-Royce, Saab, Kawasaki, KAL-ASD, Fuji, Goodrich, Alenia Aeronautica, Missier-Dowty, Latecoer, and Spirit AeroSystems (which was spun-off from Boeing in 2005), and asked them not just to produce the part, but to design an aspect of the new aircraft as well. Essentially, Boeing would offload most of the 787 Dreamliner's development costs to its suppliers.

Similar to the MD-95, in order to win the 787 Dreamliner contract, suppliers needed to take on the bulk of the upfront development costs, with the hope of making the money back over the years through the sale of parts, repairs, and maintenance to Boeing, airlines, and airline leasing companies. It wasn't a great deal, but they didn't really have a choice, with Boeing holding enormous negotiating leverage as one-half of the global commercial aircraft duopoly.

The 787 was first announced in 2003. By 2005, there were hundreds of orders in, but deliveries were delayed by three years. On 7/8/07, Boeing debuted its first Dreamliner in a photo-op for reporters and dignitaries, but it was essentially a shell lacking a floor, wiring, systems, or plumbing. Two-and-a-half years later, in 2010, after six delays in aircraft delivery, test flights of the aircraft began.

The first 787 was officially delivered to the Japanese airline All Nippon Airways (ANA) in September 2011. Soon after, Boeing's warranty woes began. In the fourth quarter of 2011, right after those first commercial 787s were delivered, Boeing tripled its warranty accruals. Accruals surged in 2012, peaking in the fourth quarter of the year. In 2010, Boeing set aside $141 million in warranty accruals; in 2012, Boeing set aside $890 million in warranty accruals, including the additional changes of estimate made in the second and third quarters of the year.

Boeing's Warranty Costs

Instead of just telling you about it, let's take a look at the manifestation of these warranty problems in the following charts, which show the warranty expenses of Boeing from 2003 until the most recent quarter, the third quarter of 2025.

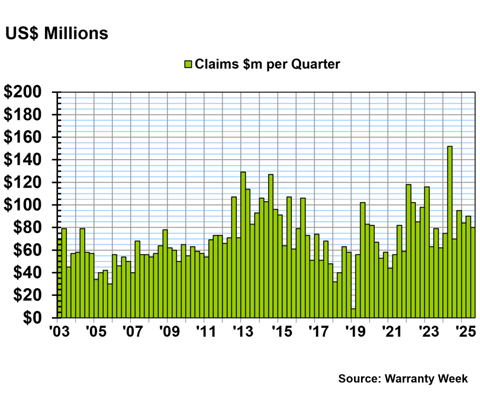

Figure 1 shows Boeing's quarterly warranty claims paid, from 2003 to the third quarter of 2025. Notice the dual peaks, one from 2013 to 2015, related to the 787 Dreamliner, and one from 2019 to present, related to the 737 MAX 8 and 9.

Figure 1

Boeing Co.

Claims Paid per Quarter

(in millions of U.S. dollars, 2003-2025)

Since 2003, the most costly quarter for Boeing, in terms of warranty claims paid, was the second quarter of 2024. In that quarter, Boeing paid $152 million in warranty claims.

Other notable quarters related to the 737 MAX warranty problems include the first quarter of 2022, where Boeing paid $118 million in claims, and the first quarter of 2023, where Boeing paid $116 million in claims. Another notable quarter, at the beginning of the initial round of 737 MAX groundings, was the third quarter of 2019, when Boeing paid $102 million in claims.

Related to the 787 Dreamliner warranty issues, Boeing saw spikes in warranty claims costs in 2013 and 2014. In the first quarter of 2013, Boeing paid $129 million in warranty claims, and in the third quarter of 2014, Boeing paid $127 million in claims.

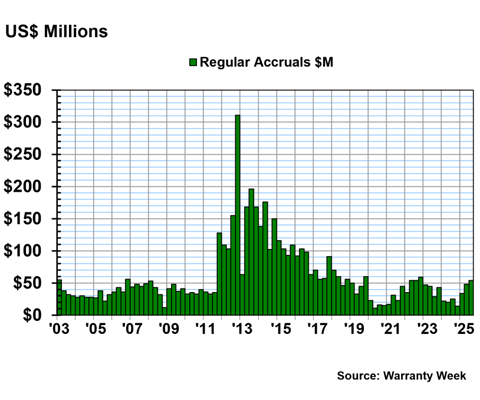

Figure 2 shows the total quarterly warranty accruals made by Boeing, from 2003 to the third quarter of 2025.

Figure 2

Boeing Co.

Accruals Made per Quarter

(in millions of U.S. dollars, 2003-2025)

We can see that by far, Boeing set aside the largest sum in warranty accruals in the fourth quarter of 2012. Boeing set aside $311 million in warranty accruals in that single quarter, related to the warranty costs that arose from the issues with the 787 Dreamliner.

Around that single quarter, we can see elevated warranty accruals from the beginning of 2012, until early 2015.

The obvious question here is, why can't we see the warranty costs from the 737 MAX groundings on this chart as well? The answer is that Boeing changed how it conducts its warranty accounting around groundings after the 787 Dreamliner issues.

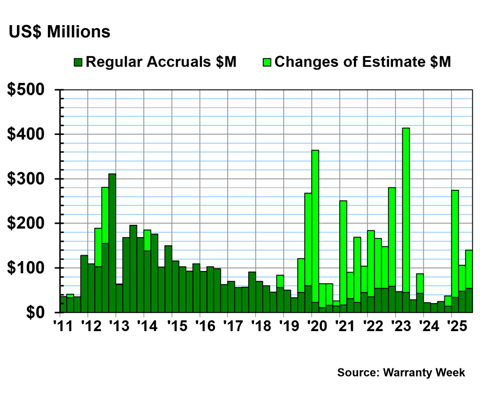

In Figure 3, the data in dark green are the same as those presented in Figure 2. However, the data in light green show changes of estimate to previous accruals. Basically, changes of estimate are additional accruals that are made to adjust previous accruals, rather than new warranty accruals. For the 737 MAX groundings, Boeing accounted for the additional warranty expenses as adjustments to previously made accruals.

In short, these changes of estimate were Boeing setting aside extra funds, after reaizing that it had not set aside enough money at the time of the sale of these aircraft. Figure 3 shows regular accruals and changes of estimate made by Boeing, from 2011, when the 787 Dreamliner issues began, until the third quarter of 2025.

Figure 3

Boeing Co.

Accruals & Changes of Estimate Made per Quarter

(in millions of U.S. dollars, 2011-2025)

With the changes of estimate included in this chart, we can see that the 737 MAX groundings were far costlier than the 787 Dreamliner issues were.

In the fourth quarter of 2019, Boeing set aside $60 million in regular warranty accruals, and an additional $208 million in changes of estimate. In the first quarter of 2020, Boeing set aside just $23 million in warranty accruals, but an additional $341 million in changes of estimate.

In the first quarter of 2021, Boeing set aside just $17 million in warranty accruals, and an additional $234 million in changes of estimate. In the fourth quarter of 2022, Boeing set aside $59 million in regular accruals, and an additional $221 million in changes of estimate. And in the second quarter of 2023, Boeing set aside $45 million in regular accruals, and an additional $369 million in changes of estimate.

Overall, from 2019 to 2024, including a few negative adjustments as well, Boeing set aside $2.06 billion in changes of estimate to previous accruals. That's quite a significant under-estimation of what the warranty costs associated with its aircraft, specifically the 737 MAX, would be.

More recently, in the first quarter of 2025, Boeing set aside $34 million in regular accruals, and an additional $240 million in changes of estimate. In the second quarter of 2025, Boeing set aside $48 million in regular accruals, and $58 million in changes of estimate. And in the third quarter of 2025, Boeing set aside $54 million in regular accruals, and an additional $86 million in changes of estimate. The company's changes of estimate have exceeded regular accruals since the fourth quarter of 2024.

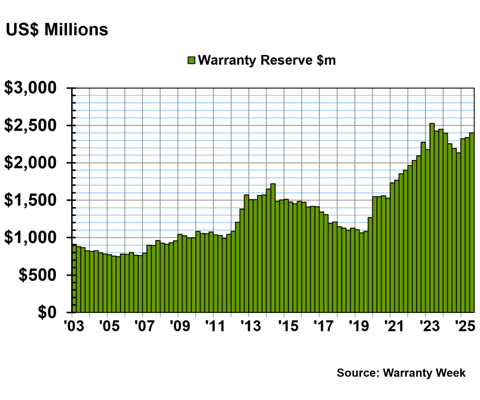

Figure 4 shows the quarterly end-balance of the warranty reserve fund of Boeing, from 2003 to 2025.

Figure 4

Boeing Co.

Reserves Held per Quarter

(in millions of U.S. dollars, 2003-2025)

Boeing's warranty reserve balance hit a record high in the second quarter of 2023, at $2.53 billion.

At the end of the most recent quarter, the third quarter of 2025, Boeing held $2.40 billion in warranty reserves.

Airbus

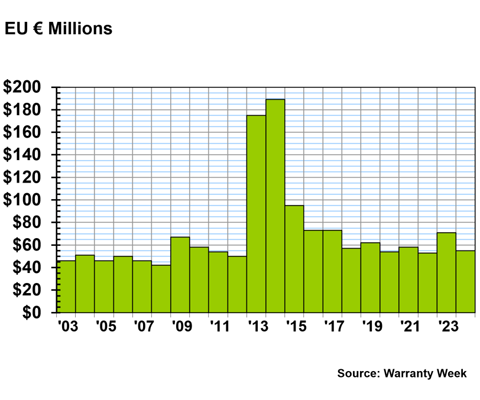

The following three figures show Airbus' annual warranty expenses. Figure 5 shows the total annual warranty claims paid by Airbus in Euro, from 2003 to 2024.

Figure 5

Airbus SE

Claims Paid per Year

(in millions of Euro, 2003-2024)

We can clearly see the warranty costs associated with the issues with the Airbus A380 in 2013 and 2014 in Figure 5. In 2013, Airbus paid €175 million in warranty claims, and in 2014, Airbus paid €189 million in claims.

In 2024, Airbus paid €55 million in warranty claims.

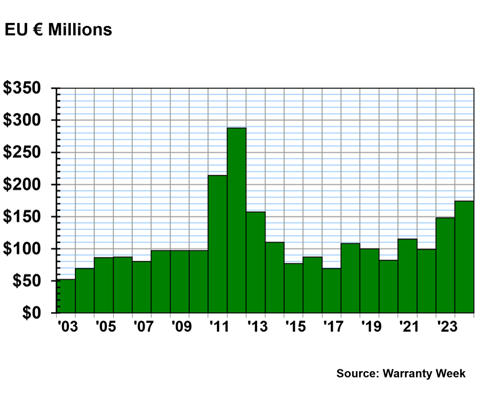

Figure 6 shows Airbus' total warranty accruals from 2003 to 2024.

Figure 6

Airbus SE

Accruals Made per Year

(in millions of Euro, 2003-2024)

In 2011, Airbus set aside €214 million in warranty accruals. In 2012, Airbus set aside €288 million in warranty accruals, and in 2013, Airbus set aside €157 million.

In 2023 and 2024, total warranty accruals rose back to a similar level, likely due to inflation. In 2024, Airbus set aside €174 million in warranty accruals.

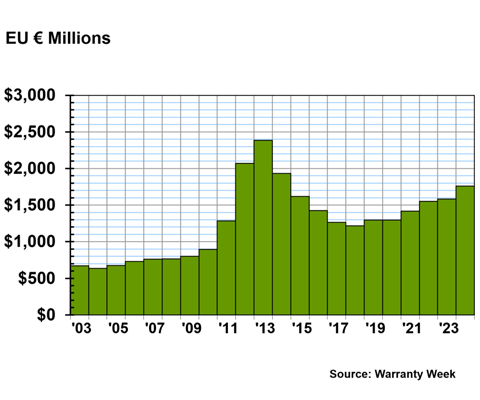

Figure 7 shows Airbus' warranty reserve balance at the end of each fiscal year, from 2003 to 2024.

Figure 7

Airbus SE

Reserves Held per Year

(in millions of Euro, 2003-2024)

Airbus' warranty reserve balance peaked in 2013, at €2.39 billion. At the end of 2024, Airbus held €1.76 billion in warranty reserves.